Abigail Lindo

Brandon Katzir, Smith College

The revival of Hebrew from a language used by erudite scholars to a modern vernacular owes much to Eliezer Ben-Yehuda, a linguistic savant and experimentalist who is widely credited with “updating” the Hebrew language for modern life at the turn of the century. Ben-Yehuda wrote the 17-volume “Complete Dictionary of Ancient and Modern Hebrew,” founded the Hebrew Language Council, the forerunner to the still-extant Hebrew Language Academy, and was so committed to the language that he raised his two children without exposing them to any language other than Hebrew—surely a feat in late nineteenth-century Ottoman Palestine where Russian, Yiddish, Arabic, and Turkish were sometimes supplemented by French to form a polyglot society. But decades before Ben-Yehuda’s dictionary, Abigail Lindo (1803–1848) became the first woman to write a Hebrew dictionary, printing her Hebrew and English Dictionary in 1837. Lindo was both the first British Jew to compile a Hebrew-English dictionary and the first woman to print a dictionary under her own name in Great Britain.

Lindo’s dictionary was privately circulated and, unfortunately, she does not include a raison-d’etre for the volume in her introduction, though she did indicate that she hoped her dictionary would be adopted at Jewish schools in Britain. But what stands out about Lindo’s dictionary is that she creates a variety of modern Hebrew words out of classical roots. Thus, her dictionary not only defines familiar words found in Jewish scripture, but adds words like “chicken-pox,” “gunpowder,” “gazette,” and “wardrobe.” Lindo makes skillful and creative use out of the Hebrew root structure to develop linguistically-based neologisms for practical use. While few of her innovations were adopted in modern Hebrew, Lindo’s work nonetheless demonstrates the move toward Hebrew as vernacular that was beginning to take root in the Jewish world of the nineteenth century.

Biography

Abigail Lindo was born in 1803, the fifth of 18 children of David and Sarah Abarbanel, prominent community leaders and scions of the Sephardic mercantile families who were among the first Jewish families to move to Britain after the readmission of the Jews in the seventeenth century. Lindo had a personal relationship with her older cousin, Sir Moses Montefiore, and she was a distant relative of Maria Basevi, the mother of Benjamin Disraeli. Incidentally, according to the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Lindo’s father performed Disraeli’s ritual circumcision on 28 December, 1804. Her family were important members of the Bevis Marks Synagogue; her uncle, Moses Mocatta, was a well-respected scholar and writer on Jewish issues, and her cousin, Elias Haim Lindo, was one of the first contemporary historians of nineteenth-century Anglo-Jewry.

Given this family history, it is unsurprising that Lindo took up scholarly pursuits herself. She reports studying both with her father and her uncle, and her writing and scholarly acumen was remarked upon by the Dayan (the de facto Chief Rabbi) of the Sephardic community, Rabbi David Meldola, a scholar in his own right. Lindo seems first to have written her dictionary to aid in her own study of the Hebrew language and Judaic texts. As she began to share her work with friends and fellow scholars, they encouraged her to publish it, which she did in 1837. She published an expanded edition in 1842 and an even more robust Hebrew-English dictionary in 1846. Her dictionary included a list of common Hebrew abbreviations, a typical stumbling block for those learning rabbinic texts, as well as practical dialogue. Beginning with the second edition, her works were used in Jewish schools and came with the hashkafa—the religious and scholarly approval—of Meldola. Lindo was frequently ill and died in 1848 at 45 years old. She was mourned by the Sephardic community as well as Anglo-Jewish scholars, and Meldola published and recited a Hebrew-English dirge at the Bevis Marks Synagogue in commemoration of her life. Lindo is credited with being the only women in the nineteenth-century to have published works on biblical philology and Hebrew-language lexicography.

Status of Hebrew in Lindo’s Lifetime

Though the Hebrew language has been used by Jews since antiquity, it has, since Biblical times, been supplanted by various vernacular languages for everyday speech. While Hebrew-inflected dialects of diasporic languages (Aramaic, Arabic, German, and Spanish come to mind) often functioned as modes for everyday speech and the Hebrew alphabet functioned as the mechanism for writing in those languages, the Hebrew language itself was reserved for prayers, formal contracts involving Jewish law, and religious texts for study. This began to change beginning in the late eighteenth century with the Haskalah, the Jewish Enlightenment, especially as the Haskalah became intertwined with debates about nationhood and national identity. It is important to understand that Lindo’s dictionary was written in the opening decades of a resurgence of interest in Hebrew as a language not just in the religious realm, but in secular literature, in political writing, and in the scholarly chatter of cafes from London to Saint Petersburg. Within a decade of Lindo’s death in 1848, at least 9 nationally or internationally distributed Hebrew-language newspapers and journals were founded with offices in Odessa, Saint Petersburg, Warsaw, Berlin, Brody, Krakow, Vienna, Lviv, Jerusalem, Paris, Mainz, London, and Vilna. Lindo’s understanding of Hebrew usage—especially a Hebrew that can be used conversationally, a Hebrew that is taught in Jewish schools to all children, boys and girls, is at the forefront of a revolution on how the language’s use would radically change in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

Lindo’s Dictionary

Most nineteenth-century dictionaries contain lengthy introductions that discuss editorial decisions, philological concepts, usage variations and regional dialects, etc., but unfortunately Lindo gives us little insight into her lexicographical philosophy. But the structure of her dictionary gives us some clues as to her audience and her perception of their needs in a Hebrew dictionary. Her preface explains that the dictionary is broken into three parts: Part I consists of the words most frequently used in Hebrew and English. Curiously, she does not say specifically whether she means the most popular Hebrew or English words, but it quickly becomes clear that she means both. Additionally, Hebrew verbs have a triliteral root structure, and Lindo identifies the triliteral root words in her dictionary—this not only helps readers understand the relationship between words, it also, as Lindo notes, allows them to “consult the celebrated works of Buxstorf, Parkhurst, Gesenius, Furst, and other eminent Lexicographers” who normally ordered their dictionaries with the root word.

Figure 1: Sample page, Part I

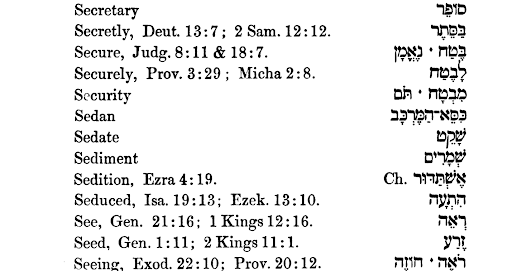

In Part II, Lindo presents a list of alphabetized words, provides notes on whether those words are rabbinic, and gives citations for those which appear in the Hebrew bible. Most of the words have some Biblical reference or are marked “Rab.,” meaning they derive from Rabbinical Hebrew. Interestingly, some bear no marking. Perhaps, like “mitachat,” or “under,” they are so ubiquitously used that Lindo does not believe a citation is necessary or perhaps she is unclear as to the origin of some of the terms in the dictionary. She defines “sedan chair,” for example, as a “kiseh hamerkav,” literally a seat of the chariot, but there is no usage cited of these terms together in this way. The term is used, however, in later Jewish mystical literature, so it’s possible she’s defining a term she has encountered in her studies but does not have a textual reference for the term either in the Tanakh or in the classical corpus of rabbinical literature. A good example of a Rabbinic usage she identifies is a word that she translates to English as “bishop.” Unfortunately, Lindo doesn’t supply any specific citations in rabbinical literature, so it is nearly impossible to follow her translation logic for some of the terminology.

Figure 2: Sample page, Part II

Finally, Part III comprises a list of abbreviations common in Hebrew language texts, some in the Bible, most in rabbinical literature. Even skilled readers of classical Hebrew struggle with the vast number of textual abbreviations in the rabbinic corpus, and so having a guide like Lindo’s is incredibly valuable even for advanced students of the Talmud. Part III is nearly 20 pages long.

Figure 3: Sample page, Part III

So, while there is no formal introduction describing lexicographical principles, it is clear that Lindo’s dictionary is designed for multiple audiences. For those familiar with the Hebrew language and its grammar, it includes frequently used words in Hebrew and gives their root structure, which would enable a student to look for the word in a Hebrew concordance or in an etymological dictionary (and Lindo even lists those dictionaries she finds to be worthwhile). For those looking for alphabetized words in Hebrew and where they appear in the Tanakh, she provides a large dictionary of words complete with scriptural references and also includes Hebrew popular in the Jewish lexicon that are rabbinic in origin. And finally, for those engaged with rabbinic treatises or Talmudic study, she includes 20 pages worth of acronyms and abbreviations to aid readers with the higher level jargon that accompanies rabbinical writing. While some of Lindo’s innovations are in general use—she calls gunpower, for example, “avak ha-soref,” literally “the burning dust,” which is the modern term today in Israel—others innovations were not used. It is clear from Lindo’s etymologies that she is not familiar with Aramaic or Arabic, which have both had an enormous influence on the modern Hebrew lexicon—Ben-Yehudah in particular would borrow extensively from the vast corpuses of Jewish Aramaic when constructing his dictionary, and the fact that roughly 60% of the Israeli Jewish population are the children and grandchildren of refugees from the Arabic-speaking world has meant the importation of a sizable Arabic lexicon which, in any event, bears close similarity to Hebrew already.

Despite the fact that the modern language continued to evolve in ways that Lindo could not have foreseen, she had remarkable foresight in acknowledging the role that Hebrew played in Jewish life and would continue to play. Her insistence on including Hebrew translations of words used in a middle-class Victorian milieu demonstrates a fidelity to the language beyond the beit midrash—the study hall—a philosophy which included both men and women, sages and novices, the synagogue and the salon, and psalms and sedan chairs.

Works Consulted

Mandel, George. “Why Did Ben-Yehuda Suggest the Revival of Spoken Hebrew?” Hebrew in Ashkenaz: A Language in Exile, edited by Lewis Glinert, pp. 193–207, Oxford UP, 1993.

Mugglestone, Lynda. “The Victorian Novel and the OED.” The Oxford Handbook of the Victorian Novel, edited by Lisa Rodensky, pp. 147–65, Oxford Handbooks, Oxford UP, 2013.

Rodrigues-Pereira, Miriam. “Lindo, Abigail (1803–1848), Lexicographer.” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, 17 Sept. 2015.

Shivtiel, Avihai. “Languages in Contact: The Contribution of the Arabic Language to the Revival of Hebrew.” Journal of Semitic Studies, vol. 30, 1985, p. 95.

Sijens, Hindrik, and Hans Van de Velde. “The Formation of Neologisms in a Lesser-Used Language: The Case of Frisian.” Dictionaries: Journal of the Dictionary Society of North America, vol. 41, no. 1, 2020, pp. 45–67.

Sivan, Reuven. “Eliezer Ben-Yehuda and the Revival of Hebrew Speech.” Leshonenu La-‘Am, vol. 24, 1972–73, pp. 67–116.

Taylor, Dennis. “The Body of Victorian Language and the Hunting of the OED.” Annals of Scholarship: An International Quarterly in the Humanities and Social Sciences, vol. 7, no. 2, 1990, pp. 155–63.

Bibliography